Published

Bleeding

Published

Published

For a kid raised in the humid, sup-tropical climate of Queensland, blankets of fallen leaves only existed in books and films. Come January I’ll have resided in Europe for a decade but the novelty hasn’t worn off.

Published

Monet’s Water Lilies are one of very few works of art that have physically overwhelmed me on viewing. The life-sized canvases are entirely mesmerising, ‘no sky, no horizon, hardly any perspective or stable points of reference enabling the viewer to orient himself…’.

The intimacy is heightened further by their 360 degree installation in the two sequential oval rooms of Musée de l’Orangerie. On entering the second room, we found ourselves entirely alone – due to pandemic-related travel restrictions. The deserted room was an unexpected gift and truer to the artist’s original intent for the viewer:

Those with nerves exhausted by work would relax there, following the restful example of those still waters, and, to whoever entered it, the room would provide a refuge of peaceful meditation in the middle of a flowering aquarium.

Claude Monet, 1909

Published

A loop walk from Bruton, early August.

Published

We have wanted to visit Oudolf Field for awhile and last weekend made it happen. During lockdown we’d primed ourselves with Five Seasons: The Gardens of Piet Oudolf, but nothing compares to the real thing.

The Oudolf Field is masterfully planted, taking into account colour, shape, texture and height to frame nature as both sculpture and theatrical performance. Time congeals in the garden, as if its entrance is a portal to an over-cranked film. Bodies parade in slow motion to find every vantage point and appreciate every contrast. The best part is that nature takes no pause. I look forward to returning in autumn, winter and spring.

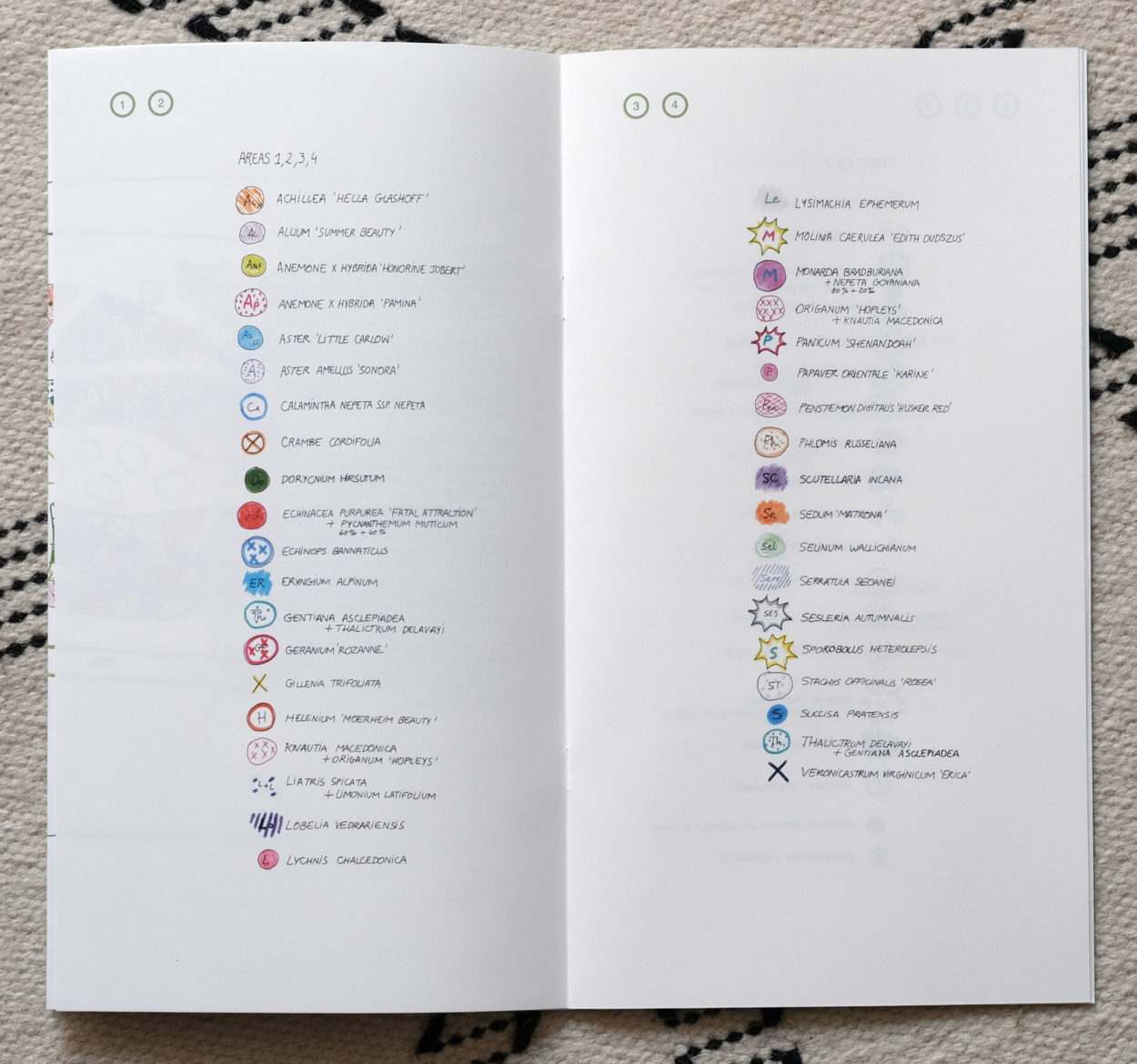

Over the course of his gardening practice, Piet Oudolf has developed an informal, but intricately detailed, approach to planning. Colour and pattern, seemingly haphazard, enables an agility in application. His hand-drawn sketches are beautiful objects in their own right, appealing to any graphic designer that is seduced by intelligent, orderly systems.

Published

MR took me to Kettle’s Yard for my birthday ? without either of us knowing too much about it. I had seen the identity developed by Apfel, and our landlord Nina had mentioned it. Excerpts on its history from the website below.

Between 1958 and 1973 Kettle’s Yard was the home of Jim and Helen Ede. In the 1920s and 30s Jim had been a curator at the Tate Gallery in London. Thanks to his friendships with artists and other like-minded people, over the years he gathered a remarkable collection, including paintings by Ben and Winifred Nicholson, Alfred Wallis, Christopher Wood, David Jones and Joan Miró, as well as sculptures by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Constantin Brancusi, Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth.

At Kettle’s Yard Jim carefully positioned these artworks alongside furniture, glass, ceramics and natural objects, with the aim of creating a harmonic whole. His vision was of a place that should not be

“an art gallery or museum, nor … simply a collection of works of art reflecting my taste or the taste of a given period. It is, rather, a continuing way of life from these last fifty years, in which stray objects, stones, glass, pictures, sculpture, in light and in space, have been used to make manifest the underlying stability.”

Kettle’s Yard was originally conceived with students in mind. Jim kept ‘open house’ every afternoon of term, personally guiding visitors around his home. In 1966 he gave the House and its contents to the University of Cambridge. In 1970, three years before the Edes retired to Edinburgh, the House was extended, and an exhibition gallery added. The House is by and large as Jim left it. There are artworks in every corner, and there are no labels.