Published

How to grow a garden

The other week m cheerily called ‘Hallo!’ from her first floor window to a passerby who, by chance, happened to have slept in the very same bedroom as a child. Our house had belonged to her mother, and the raised bed sleepers in the back garden had been placed by her father decades earlier. For the three growing seasons the house has been ours the decayed sleepers and an arch sat like oversized furniture making the space feel unfairly small, exacerbated further each spring as nature trickled into a torrent of unruly green.

Since January M and I have been in the back courtyard most weekends. While dyschronia places me in late summer I happily accept the reality that we’re only mid-Spring. In reconfiguring the garden, our wishes were simple – a sense of spaciousness, low maintenance planting, easy access to the garage, and areas for lounging, barbecuing and play. And unlike other DIY projects undertaken in the house, nature’s impermanence has made for a liberating playground.

Noting here some useful resources and lessons learned through the process:

How to select plants

- Book Planting the Natural Garden by Piet Oudolf & Henk Gerritsen

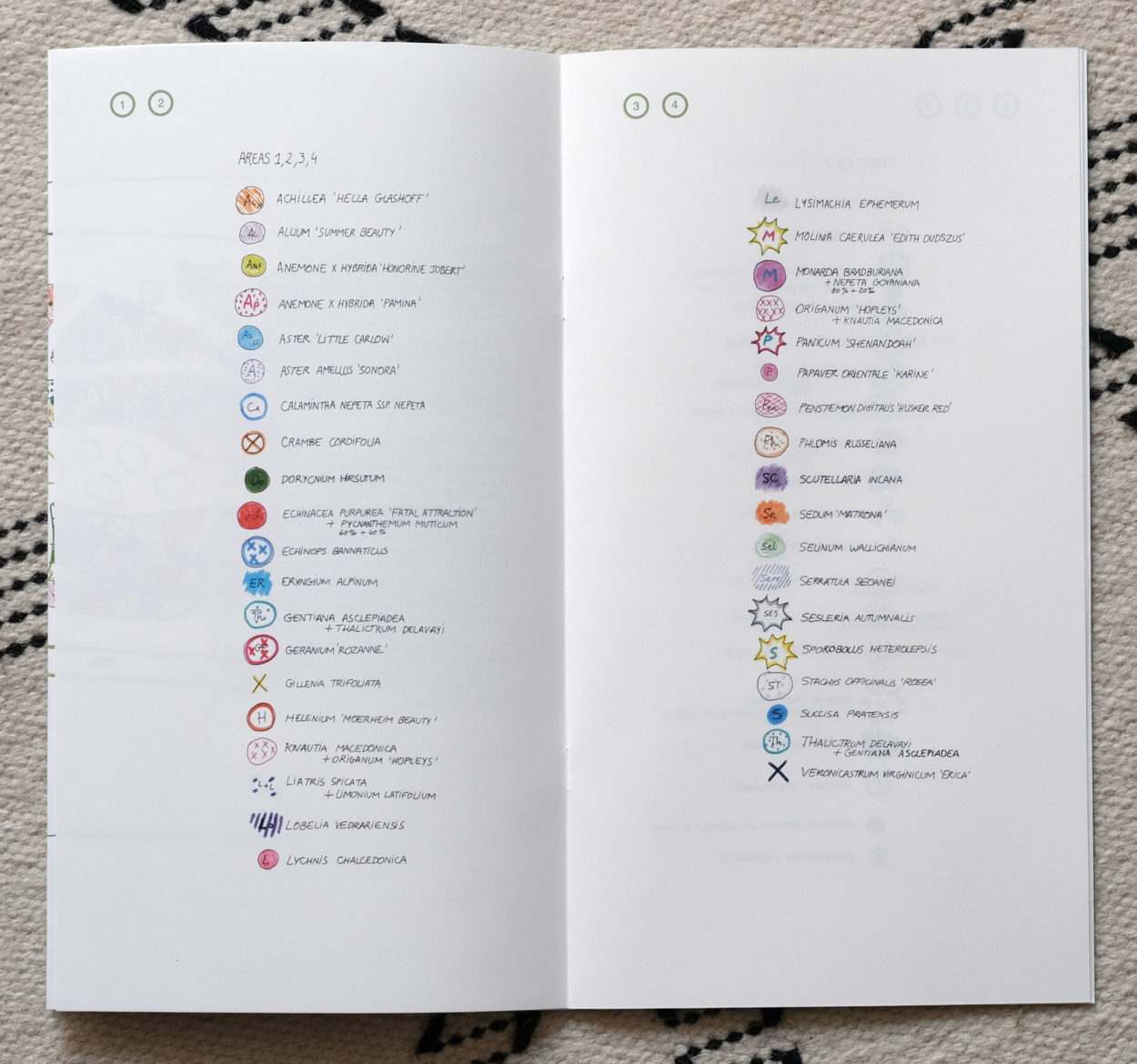

This book offers pretty comprehensive detailing of Oudolf and Gerritsen’s favourite perennial plants and grasses, along with some planting theme suggestions and spacing recommendations. I read it like a novel and revered it like a bible, slowly refining a final selection of plants for our space. The ’New Perennial’ or ‘Dutch Wave’ movement that Oudolf is renowned for choreographs plants and grasses, taking into consideration their bloom period, season by season structure, colour and height to create a display that’s interesting in every season. - Gardener Erik Funneman

Erik was one of several gardeners available for speed dating sessions as part of the Utrecht Botanic Gardens voorjaarsweekend program. With some luck, we were able to get some guidance from him on plant selection, with recommendations to limit variety of species for greater impact and substitute some current selections for close variants that were lower maintenance. I particularly like the sculptural elements in his work – whether built construction or via plant selection and combination.

Where to source them (and other plant-related things)

- Nurseries Plantwerk, van Houtem, and de Hessenhof

In hindsight, though Planting the Natural Garden was an essential primer, I realise now that it is more practical to have a base knowledge of plants which can then be drawn on to select from the growing lists of one or two preferred nurseries – making for simple procurement and confidence in quality. Buying directly from nurseries, as opposed to garden centres, provides better insight regarding the origins of your plants. Both organically grown and native plants contribute to biodiversity through improved soil quality and by supporting pollinators, respectively. - Bases and toppers Biokultura and Pokon

Biokultura is run by Kwekerij van Houtem and produces high-quality organic potting soil, garden soil and compost. We filtered our existing soil, which tested neutral and already had a decent ecosystem of worms and bugs, and mixed it with some of Biokultura’s garden soil to improve it a little more. It has barely rained since our plants went in the ground, so Pokon’s mulch has been extremely helpful in retaining moisture (and minimising weeds). - Tuinderijen Eykenstein and Amelis’Hof

In Utrecht the distance between the city centre and its outer boundaries is small, making it possible to live in urban areas and take a short cycle to buy organic fruit, veg and flowers directly from small growers. This is a small pleasure, that I hope to make more of a practice – a beautiful cycle for fresh groceries making for a slow Saturday morning.