Published

Bruton loop walk

A loop walk from Bruton, early August.

Remnants from personal experiences

Published

A loop walk from Bruton, early August.

Published

We have wanted to visit Oudolf Field for awhile and last weekend made it happen. During lockdown we’d primed ourselves with Five Seasons: The Gardens of Piet Oudolf, but nothing compares to the real thing.

The Oudolf Field is masterfully planted, taking into account colour, shape, texture and height to frame nature as both sculpture and theatrical performance. Time congeals in the garden, as if its entrance is a portal to an over-cranked film. Bodies parade in slow motion to find every vantage point and appreciate every contrast. The best part is that nature takes no pause. I look forward to returning in autumn, winter and spring.

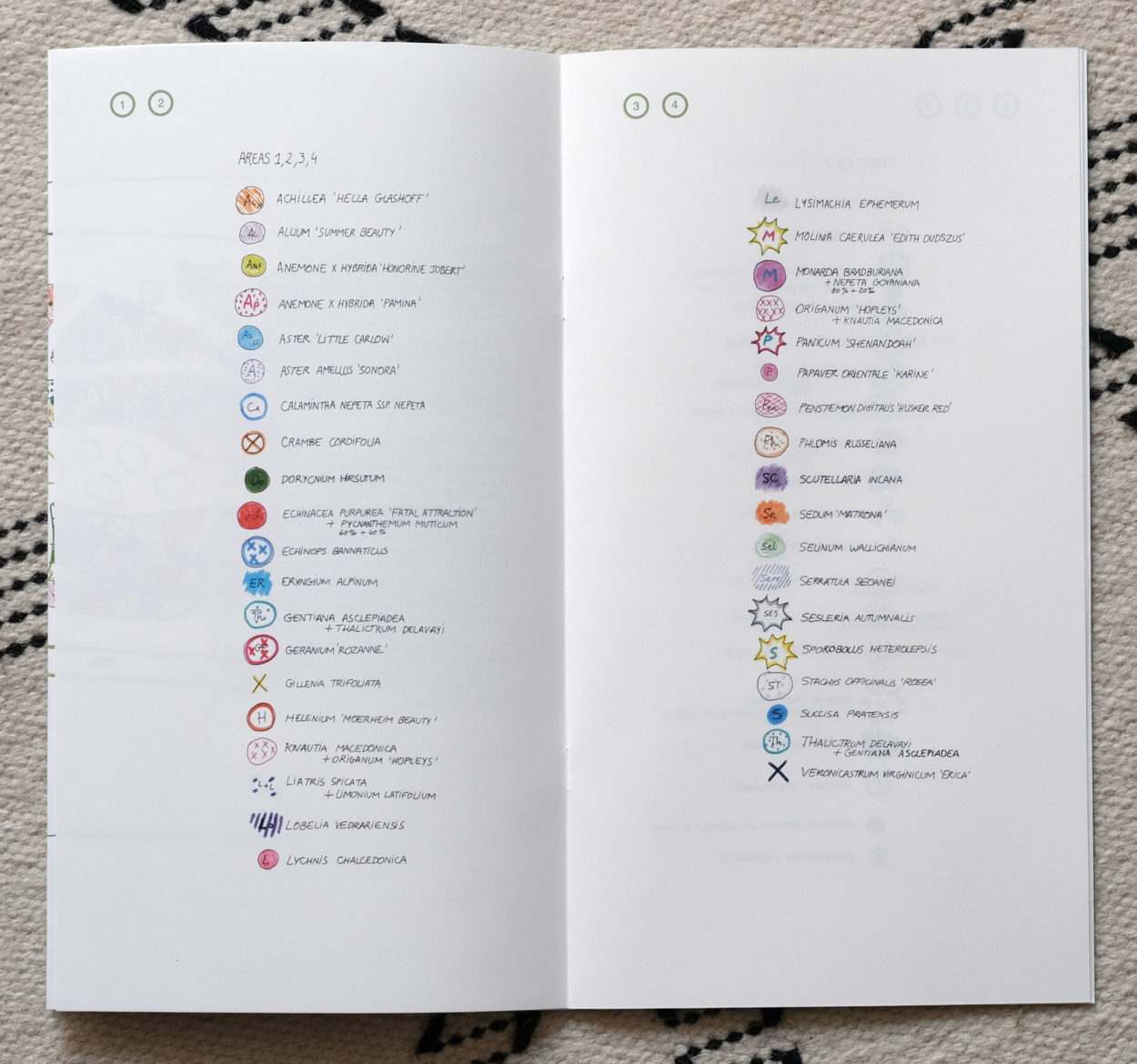

Over the course of his gardening practice, Piet Oudolf has developed an informal, but intricately detailed, approach to planning. Colour and pattern, seemingly haphazard, enables an agility in application. His hand-drawn sketches are beautiful objects in their own right, appealing to any graphic designer that is seduced by intelligent, orderly systems.

Published

No single word can accurately capture the strangeness of 2020. MR and I have been extremely fortunate that we have, in the scheme of things, been relatively unaffected by the Coronavirus Pandemic. Our jobs – and income – have remained unchanged, and we have a dedicated workspace at home each with a comfortable desk and chair. We have no children that require entertaining or educating, nor any elderly family living locally in need of care. We have had the privilege of access to food, physical space, face masks, hand sanitiser and soap, unlike a large proportion of the developing world.

Despite our privilege, I am weary. In January, scaffolding went up around the Victorian terrace next to ours, ahead of a major reconstruction which gutted the property and added a floor. Aside from two weeks in early April, due to government restrictions on non-essential work, the renovation has charged forward. Hammering, drilling, sanding, sawing, has been the soundtrack of the last six months meaning that almost all of my work video calls have required me muting and briefly unmuting my microphone to contribute to the conversation.

Read morePublished

The weekends are slow. The hay fever is oppressive. When evening settles and all but the birds have turned in we watch films in bed – recently, Wadjda (2012) and Big Night (1996).

Published

This jasmine crop has been a source of comfort lately. MR and I, individually or together, walk past it every day, sucking its perfume deep into our lungs and occasionally rehoming a sprig.

Published

Published

MR took me to Kettle’s Yard for my birthday ? without either of us knowing too much about it. I had seen the identity developed by Apfel, and our landlord Nina had mentioned it. Excerpts on its history from the website below.

Between 1958 and 1973 Kettle’s Yard was the home of Jim and Helen Ede. In the 1920s and 30s Jim had been a curator at the Tate Gallery in London. Thanks to his friendships with artists and other like-minded people, over the years he gathered a remarkable collection, including paintings by Ben and Winifred Nicholson, Alfred Wallis, Christopher Wood, David Jones and Joan Miró, as well as sculptures by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Constantin Brancusi, Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth.

At Kettle’s Yard Jim carefully positioned these artworks alongside furniture, glass, ceramics and natural objects, with the aim of creating a harmonic whole. His vision was of a place that should not be

“an art gallery or museum, nor … simply a collection of works of art reflecting my taste or the taste of a given period. It is, rather, a continuing way of life from these last fifty years, in which stray objects, stones, glass, pictures, sculpture, in light and in space, have been used to make manifest the underlying stability.”

Kettle’s Yard was originally conceived with students in mind. Jim kept ‘open house’ every afternoon of term, personally guiding visitors around his home. In 1966 he gave the House and its contents to the University of Cambridge. In 1970, three years before the Edes retired to Edinburgh, the House was extended, and an exhibition gallery added. The House is by and large as Jim left it. There are artworks in every corner, and there are no labels.