Published

Interdependent immunity

Our bodies may belong to us, but we ourselves belong to a greater body composed of many bodies. We are, bodily, both independent and dependent.

Eula Biss, On Immunity, pg 132

Text or images from secondary sources

Published

Our bodies may belong to us, but we ourselves belong to a greater body composed of many bodies. We are, bodily, both independent and dependent.

Eula Biss, On Immunity, pg 132

Published

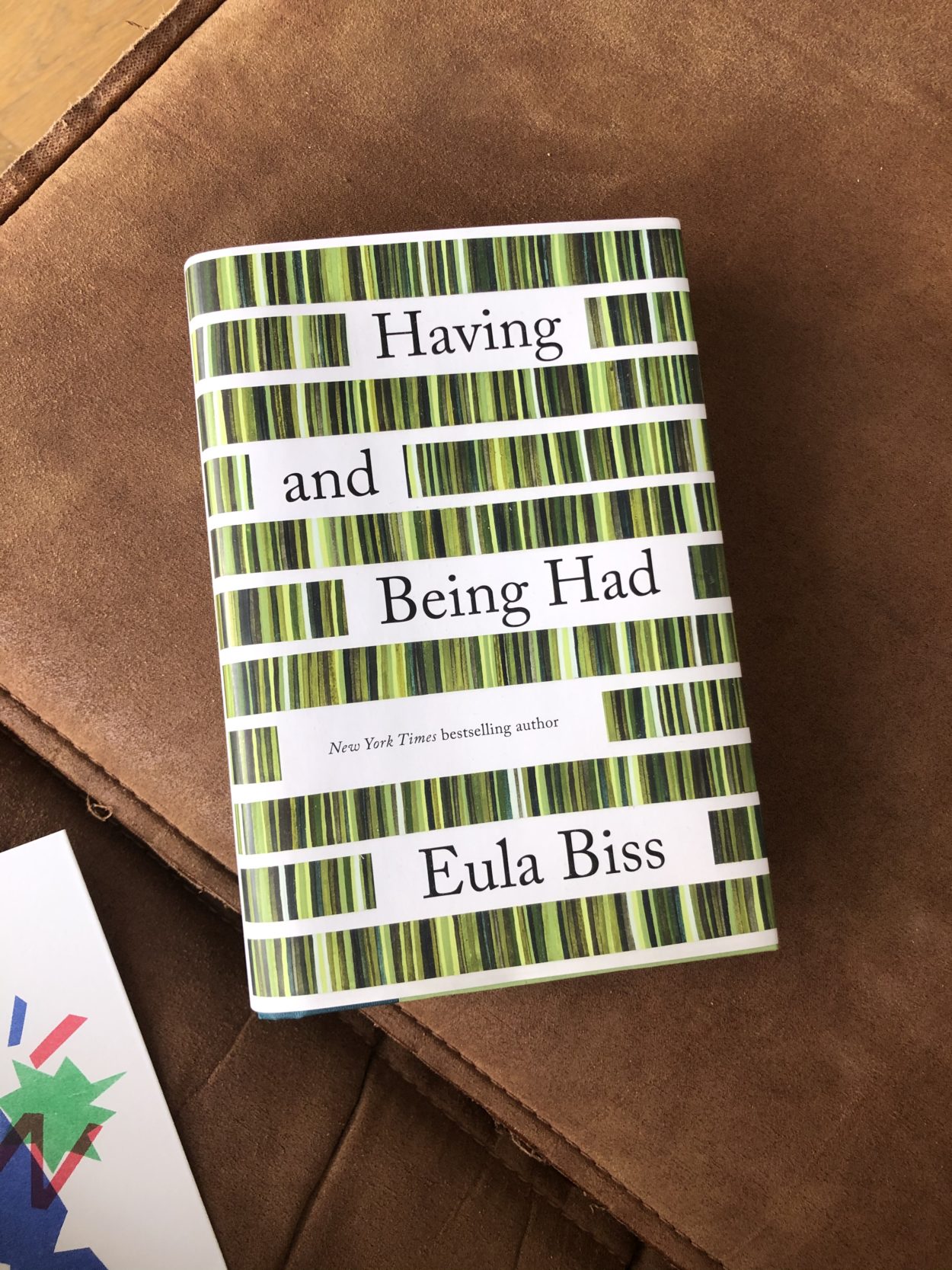

Having and Being Had is a fantastic book to read in your 30s, being both topical and refreshingly honest. Characteristically, Eula Biss rigourously weaves personal narrative with secondary research, in short chapters that make for an easy read, as she grapples with the purchase of her first home. An exemplary chapter below:

Read moreToday is Moral Monday, I hear on the radio. A priest and a rabbi are staging a protest downtown with a giant camel and a giant needle, a reference to Jesus saying, “It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God.” I pause over this, wondering if money can really be so corrupting that just having it is immoral. I have my doubts, but I also have money.

Published

Work, Lewis Hyde writes, is distinct from labour. Work is something we do by the hour, and labour sets its own pace. Work, if we are fortunate, is rewarded with money, but the reward for labour is transformation. ‘Writing a poem,’ Hyde writes, ‘raising a child, developing a new calculus, resolving a neurosis, invention in all forms—these are labours.’ This list reveals to me my problem. I want to give my life to labour, not work.

Eula Biss in Having and Being Had, pg 99

Published

In her essay ‘Suffering Like Mel Gibson’, Zadie Smith more eloquently argues what I was hacking at in ‘What we’ve lost’. In short, she suggests that the acknowledgement of suffering can be seen as an act of self-care. She writes, ‘suffering has an absolute relation to the suffering individual’ and therefore no-one has the right to judge the severity of another’s discomfort. Extracts pieced together here as a summary.

The misery is very precisely designed, and different for each person, and if you didn’t know better you’d say the gods of comedy and tragedy had a hand in it. The single human, in the city apartment thinks: I have never known such loneliness. The married human, in the country place, with partner and children, dreams of isolation within isolation … The widower enters a second widowhood. The pensioner an early twilight. Everybody learns the irrelevance of these matters next to ‘real suffering’…

Early on in the crisis, I read a news story concerning a young woman of only seventeen, who had killed herself three weeks into lockdown, because she couldn’t ‘go out and see her friends’. She was not a nurse, with inadequate PPE and a long commute, arriving at a ward of terrified people, bracing herself for a long day of death. But her suffering, like all suffering, was an absolute in her own mind, and applied itself to her body and mind as if uniquely shaped for her, and she could not overcome it and so she died…

…when the bad day in your week finally arrives – and it comes to all – by which I mean that particular moment when your sufferings, as puny as they may be in the wider scheme of things, direct themselves absolutely and only to you, as if precisely designed to destroy you and only you, at that point it might be worth allowing yourself the admission of the reality of suffering.

Zadie Smith in Intimations, pg 29

Published

Art history in particular is often cast as an almost biblical lineage, a long line of begats in which painters descend purely from painters. Just as the purely patri-lineal Old Testament genealogies leave out the mothers and even the fathers of the mothers, so these tidy stories leave out all the sources and inspirations that come from other media and other encounters, from poems, dreams, politics, doubts, a childhood experience, a sense of place, leave out the fact that history is made more of crossroads, branchings, and tangles, than straight lines. These other sources I call the grandmothers.

Rebecca Solnit in A Field Guide to Getting Lost, pg 59

Published

Thinking about the restorative quality of sunshine reminded me of the Paimio Sanatorium, completed in 1933, designed by Alvar Aalto and featuring sun terraces for tuberculosis patients. It was included in Living with Buildings, a particularly sensitive exhibition that explored the impact of architecture on wellbeing, at the Wellcome Collection last year.

Published

“She thought about how no one had taught us to grow old, how we didn’t know what it would be like. When we were young we thought of old age as an ailment that affected only other people. While we, for reasons never entirely clear, would remain young. We treated the old as though they were responsible for their condition somehow, as though they’d done something to earn it, like some types of diabetes or arteriosclerosis. And yet this was an ailment that affected the absolute most innocent.”

Olga Tokarczuk in Flights, Pg 398

Published

“…she falls asleep, too fast, exhausted from jet lag, like a lone card taken out of its deck and shuffled into some other, strange one.”

Olga Tokarczuk in Flights, Pg 308